[ad_1]

Yearly as Valentine’s Day approaches, folks remind themselves that not all expressions of affection match the stereotypes of recent romance. V-Day cynics would possibly plan a “Galentines” night for female friends or toast their platonic “Palentines” as an alternative.

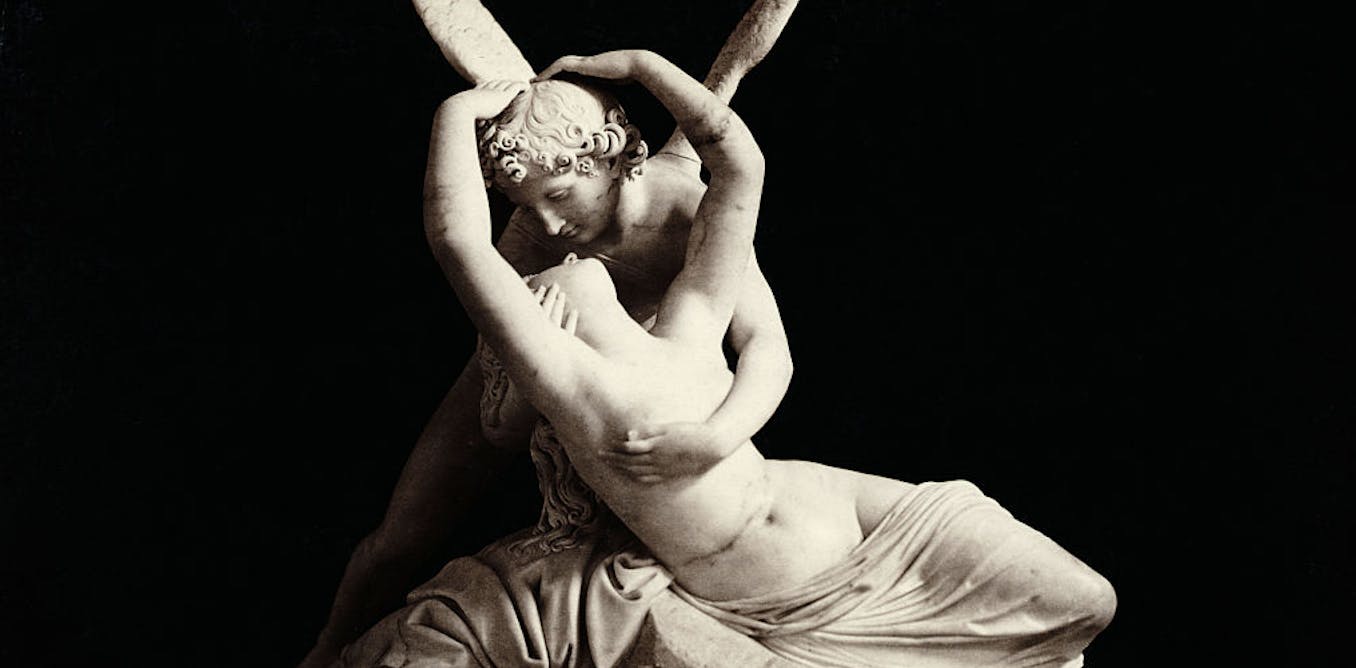

In different phrases, the vacation shines a chilly mild on the bounds of our romantic imaginations, which hew to a well-recognized script. Two persons are supposed to satisfy, the arrows of Cupid strike them unwittingly, and so they haven’t any alternative however to fall in love. They face obstacles, they overcome them, after which they run into one another’s arms. Love is a pleasant sport, and neither purpose nor the gods have something to do with it.

This mannequin of romance flows from Roman poetry, medieval chivalry and Renaissance literature, particularly Shakespeare. However as a professor of religion, I examine an alternate imaginative and prescient of eros: medieval Christian mystics who seen the physique’s wishes as instantly and inescapably linked to God, purpose and generally even struggling.

But this mind-set about love has even older roots.

My favourite class to show traces connections between eros and transcendence, beginning with historic Greek literature. Centuries earlier than Christianity, the Greeks had their very own concepts about want. Erotic love was not a pleasing diversion, however a high-stakes trial to be survived, quivering with perilous vitality. These poets’ and philosophers’ concepts can stimulate our pondering at the moment – and maybe our loving as effectively.

Lethal severe

For the traditional Greeks, eros – which could possibly be translated as “craving” or “passionate want” – was a matter of life and loss of life, even a hazard to keep away from.

Within the tragedies of Sophocles, when somebody feels eros, usually one thing is about to go terribly mistaken, if it hasn’t already.

Take “Antigone,” written in Athens in the fifth century B.C.E. The play opens with the title character mourning the loss of life of her brother Polyneices, who betrayed her father and killed her different brother in battle.

Klaus Heirler/picture alliance via Getty Images

After this civil warfare, King Creon, Antigone’s uncle, forbids residents from burying Polyneices: an insult to his reminiscence, but additionally a violation of town’s faith. When Antigone insists on burying him anyway, she is condemned to loss of life.

The play is usually interpreted as a lesson on responsibility: Creon executing the legal guidelines of the state versus Antigone defending the legal guidelines of the gods. But, uncomfortably for contemporary readers, Antigone’s devotion to Polyneices seems to be more than sisterly love.

Antigone leaps on the likelihood to die subsequent to her brother. “Loving, I shall lie with him, sure, with my liked one,” she swears to her law-abiding sister, “when I’ve dared the crime of piety.”

Had been Polyneices her husband, baby, dad or mum and even fiancé, Antigone says, she would by no means have violated the legislation. However her desire for Polyneices is so nice that she is prepared to face “marriage to Demise.” She compares the cave the place Creon buries her alive with the bed room on a marriage night time. Reasonably than starve, she hangs herself together with her personal linen veil.

Students have requested whether Antigone has too much eros or too little – and what precisely she wishes. Does she lust for justice? For piety? For her deceased brother’s physique? Her want is by some means embodied and otherworldly on the similar time, calling our personal erotic boundaries into query.

Ultimately, Creon’s ardour for civic order consumes him as effectively. His son, Antigone’s fiancé, stabs himself in grief as he embraces her corpse – and listening to of this, his mom kills herself as effectively. Eros races through the royal family like a plague, leveling all of them.

No marvel the refrain prays to the goddess of affection, pleading for defense from her violent whims. “Who has you inside him is mad,” the refrain laments. “You twist the minds of the simply.”

Embrace the chance

This results in a second lesson from the Greeks: Love would possibly make you a greater individual, nevertheless it additionally won’t.

Reasonably than converse in his personal voice, the thinker Plato wrote dialogues starring his instructor, Socrates, who had lots to say about love and friendship.

In one dialogue, “Lysis,” Socrates jokes that if all you need is romantic love, the perfect plan is to insult your crush till they thirst for consideration. In one other, “Symposium,” Socrates’ younger pupil Phaedrus imagines an indomitable military completely comprising folks in love. What braveness and energy they’d showcase for one another!

Art Images/Hulton Fine Art Images via Getty Images

In the “Phaedrus” dialogue, silly lovers search a friends-with-benefits association, afraid of the unwieldy passions that include falling in love. Socrates entertains their query: Is it higher to separate affection from sexual entanglements, because the power of want can erode one’s moral ideas?

His reply is emphatically “No.” For Socrates, sexual attraction steers the soul towards divine goodness and sweetness, simply as nice artwork or acts of justice can do.

The concept of mates with advantages, he warns, cleaves the moral self from the erotic self. Right here and elsewhere, Plato insists that to be entire folks, we should embrace the dangers that include love.

A vital insanity

Socrates has yet one more lesson to show. Erotic love is certainly a type of insanity – however a insanity vital for knowledge.

In “Phaedrus,” Socrates means that love is a insanity given by the gods, a hearth blazing like inventive inspiration or sacred rites. Sexual want disorients us, however solely as a result of it’s reorienting lovers towards one other world. The “objective of loving,” according to one dialogue, is to “catch sight” of pure magnificence and goodness.

In erotic longing we bump up towards one thing larger than us, a thread that we will hint again to the divine. And for Socrates, this pathway from eros to God is purpose. In want, a shimmer of sunshine cracks via the damaged crust of the fabric world, inspiring us to yearn for issues that final.

The modern thinker Jean-Luc Marion has instructed that fashionable educational philosophy has completely failed in relation to the topic of desire. There are huge subfields dedicated to the philosophies of language, thoughts, legislation, science and arithmetic, but curiously there isn’t any philosophy of eros.

Like the traditional Greeks and medieval Christians, Marion warns philosophers against assuming that love is irrational. Removed from it. If love seems to be like insanity, he says, that’s as a result of it possesses a “larger rationality.”

Within the phrases of one other French thinker, Blaise Pascal: “The heart has its reasons, which purpose is aware of nothing of.”

[ad_2]

Source link